The Sinking of the SS Veerhaven

by Charlie Mountain

When I signed aboard the SS Veerhaven

she was loaded with general cargo

which was destined for

various cities

in South America. We crossed the Atlantic without incident

and arrived safely at our first port of call,

Recife, Brazil.

There we learned that on August 22 while we were at sea,

Brazil had joined the Allied cause by

declaring war against Germany and Italy.

From Recife we proceeded south along the coast of Brazil to

Rio de Janeiro and

Santos. Our next port of call

was Montevideo,

Uruguay,

situated on the north

side of the famous

Rio de la Plata.

In December 1939, the

German

pocket battleship, Admiral Graf Spee,

had been scuttled off

Montevideo after being damaged in an engagement

with the British warships,

HMS Exeter,

HMS Ajax and

HMS Achilles,

and we passed by her ruins on our approach to the city.

From Montevideo we crossed to the cities of

La Plata and

Buenos Aires,

Argentina, on the south

bank of the Rio de la Plata. In those days the sprawling city of

Buenos Aires was known as the "Paris of South America".

From Buenos Aires we proceeded up the Parana River to

Rosario,

a centre for Argentina's grain industry.

After Rosario, Veerhaven left South America

for the British-governed

Falkland Islands, located

over 300 miles from the Straits of Magellan

at the tip of South America.

The Falklands, in contrast to

the various teeming cities we had visited in South America,

consisted of a

sparsely populated group of treeless, wind-swept islands

where sheep-raising was the main occupation.

Our destination was the capital and

main settlement of

Port Stanley situated on

the biggest island of East Falkland.

When we arrived we found that

were no dock facilities, as such,

in Port Stanley's harbour. All

the port had for stowing cargo was an

old sailing

ship which, I believe, had been

towed to Port Stanley

after being abandoned

somewhere about Cape Horn.

There were also no

docker at Port Stanley, and

when a ship arrived, local farmers had to leave their

farms in order to discharge the cargo themselves.

We were told that it used to take

about a month for the farmers to unload 2,000 tons of

coal blocks with each block weighing 28 pounds.

SS Veerhaven

|

|

Thank you to

Patrick Nieuwenhuis

and his father

Hank Nieuwenhuis of Holland,

for this splendid photo.

To view another photo

of Veerhaven please

Click Here. To view ship

details please

Click Here.

|

Port Stanley's

main buildings consisted of one small general store,

a church and

a small pub.

If a person needed something that was not in stock at the store,

the item had to be ordered and then brought to town by a small

ship which had a regular run to Port Stanley from the mainland.

The little church

was unusual in that outside of it there was an arch made from two

big whale bones. The other important building in town,

the pub, had been busy for two years

catering to 2,000 British soldiers who had been

stationed on the Falklands.

Some of the soldiers we met were so desperate to escape

the tedium of their lives in the lonely outpost that they

pleaded with us to to hide them

aboard the Veerhaven as stowaways. As things turned out,

it was a good thing that we didn't stow anyone away!

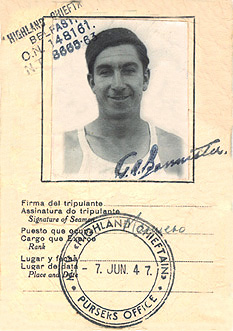

Charlie's

Landing Pass from a later visit

to

Argentina

|

After Port Stanley, we returned once more to Buenos Aires and

Rosario, Argentina,

where Veerhaven was loaded up with a cargo of

linseed destined

for the United Kingdom. Although, we didn't know it

at the time,

the linseed was to prove to be a fortunate choice. After

our holds were full, Veerhaven headed north for

the Caribbean island of Trinidad,

which was intended to be our

first stop on the way way home.

On November 10th, as we were proceeding northwards

about 800 miles off Recife, Brazil, our Radio Operator

received an

SOS

from an unidentified ship. The ship, which was

apparently somewhere ahead of us, reported

that she was being attacked by submarines. Our captain

suspected that the message was a trick designed to lure us into

a trap, so he ordered a change of course away from the

other ship's position.

The next day was November 11th -- Armistice Day -- and in the

early morning hours

I was awakened

suddenly by

the sound of heavy gunfire and machine gunfire.

I raced up on deck, but when I arrived

all I could see in the dark

were brilliant flashes coming towards the

port bow and

port beam

(the left front and side) of our ship. The flashes

were followed by explosions and fires

which broke out on the ship's deck.

We did not know until years later that we

were

being shelled

by the Italian submarine

Leonardo da Vinci

which was

under the command of the Italian ace,

Lieutenant Gianfranco Gazzana Priaroggia.

Da Vinci

had just recently arrived

in Brazilian waters with the intention of

attacking Allied merchantmen, which like us,

were travelling as independents, without naval escorts.

Beginning with the

SS Empire Zeal

which

Da Vinci sunk on November 2nd,

the submarine had also attacked the

SS Frans Hal

on November 3rd, the

SS Andreas

on November 4th, and the

SS Marcus Whitman

on November 8th. Only Frans Hal

had managed to escape her attacker -- Da Vinci

had shot five torpedoes

at the freighter, but fortunately they were all misses.

|

This photo shows the sub

Leonardo da Vinci

sometime in 1942.

Da Vinci sunk 17 Allied ships,

more any of the other Italian subs. Da Vinci's

main commander,

Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia,

was the 2nd highest scoring Italian ace with a total of 11 ships,

10 of them while he was in command of the

da Vinci.

|

|

One of the Da Vinci's victims was the CPR passenger

liner

Empress of Canada. She

was torpedoed and sunk off the Gold Coast of Africa on March 14th,

1943

with the loss of nearly 400 lives, many of them

Italian POW's.

Gazzana-Priaroggia

and all his men died on May 23rd, 1943 when Da Vinci

was sunk north-east of the

Azores

by the destroyer

HMS Active

and the frigate HMS Ness.

|

|

This photo belonging

to David Woodward is from the 1989 edition of

Jane's Fighting Ships of WWII,

published by Bracken Books, London.

|

I was a member of Veerhaven's gun crew,

so once I had arrived on deck I attempted to clamber

up to the gun platform. But, it was impossible to

get up up there because the area was being raked by machine

gun bullets. Soon it became evident that

there was nothing we could do to save the Veerhaven,

and our captain gave the order to "abandon ship".

There were two lifeboats on either side of the ship and I

was assigned to the

captain's lifeboat on the starboard

(right) side.

As we lowered the boats and were getting in them, I heard a

very big bang which I thought might might

have been an explosion in the engine room. The force

of the explosion caused Veerhaven's funnel to

lift off the deck.

Our lifeboat had a small engine as well as a sail, and as soon

as we were all

settled, our captain ordered the engine started so that we could

pull away as quickly as possible. During all this

time Veerhaven was still being fired upon, and we were

lucky

that neither our boat nor anyone in it was hit.

When daylight came, we were all saddened when we realized

that the other

lifeboat which had been launched from the

port (left) side of the ship, was nowhere in sight.

The captain then ordered

our sail to be raised and we set off for the coast of Brazil,

hundreds of miles away.

That same day we saw an aeroplane, but there was no indication that

the plane saw our tiny little speck on the ocean. Another day passed

and then on November 13th shortly before sunset, we spotted

This WWII Brazilian destroyer is from the 1989 edition of

Jane's Fighting Ships of WWII published by

Bracken Books, London.

|

the welcome sight of a

Brazilian destroyer

heading towards us.

The vessel approached us with all guns manned because

in the half-dark, the crew thought that our mast might

well be the periscope of an enemy

submarine.

When the destroyer

got closer, her crew realized that we were survivors of

an Allied ship, and they soon had us all brought safely aboard.

We managed to communicate quite well with our rescuers

and they told us that they were out on a ten-day

trial of their new American-built ship. In fact, it was the very

last day before their return to port when they spotted us.

We realized that we were very, very fortunate.

Our rescuers took us to one of our earlier ports of call,

Natal, Brazil.

Natal's location on the easternmost

bulge of Brazil's coastline

had turned out to be

a great benefit to the Allies because it

provided the shortest air route

across the Atlantic to the coast of West Africa.

Before its entry into the war the USA had

acquired various stragetic bases throughout the

Atlantic Ocean including a string of southern

airfields at

Puerto Rico,

Trinidad,

British Guiana,

Belém, and

Natal.

By time we arrived at Natal

in November 1942, the

United States

Air Transport Command (ATC)

was keeping very busy ferrying

American-built bombers and transport planes

across the Atlantic

and onward to the

Allied forces

fighting in North Africa.

The amazing

ATC

air route eventually stretched as far

as Kumming,

China,

over 14,000 miles from its start in

Florida.

After just a few days in Natal, space was found for us aboard

a military DC-3 plane which was

heading back to the United States.

|

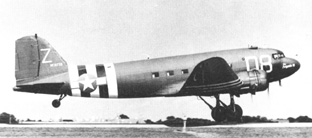

The DC-3 was a remarkable two- engined civilian aircraft which

was built in 1936 by the

Douglas Company of California.

The DC-3 was so superior to other aircraft of the time that

it soon became the number one choice of commercial

airlines around the world.

|

|

This photo of a post-war

DC-3 is from

The Encyclopedia of Aviation edited by Paul Beaver and

published by Gallery Books, NY, c1986, 1989 Octopus Books, London.

|

|

The military version of the DC-3 was the

C-47 transport

and it was just as successful

as its civilian counterpart.

The C-47 was known by a great variety of names including

Gooney Bird,

Dakota,

Dizzy-Three and

Skytrain.

|

|

This photo of an American

C-47 with D-Day invasion stripes

is from The World's Classic Aircraft by Mike Jerram,

published by Galahad Books, NY, c1981 Charles Herridge Ltd, London.

|

It was a lucky thing for us that the DC-3 had been

cleverly designed so that

it could fly on only one engine because as we flew over

the Brazilian jungle, one of our engines caught on fire.

However, the loss of the engine was not a problem and we

continued on to the American base on

the Caribbean island of

Puerto Rico where we landed

safely, appropriately enough on the American holiday of

Thanksgiving Day.

Our damaged engine was exchanged for a new one and three days after

landing at Puerto Rico we arrived at our destination of

Miami,

Florida. We caught a train which

took us up the American coast and deposited us 36 hours later

into the freezing cold weather of

New York city.

But, although the weather itself was bitterly cold,

I found that the people

there

were very warm and they made me feel very welcome.

I spent

a month in New York waiting for a ship and then signed on another

Dutch vessel, the SS Palembang.

On our way across the North Atlantic to the UK, we struck the

worst storm in fifty years. I was thrown about quite badly,

injuring both my knees and after we finally arrived in

Liverpool,

I had to spend some time in hospital recovering from my knee

injuries.

In May 1943 I signed aboard the

Dutch-flagged

SS Aelbert Cuyp

but I had to be taken off her at Hull, England and

hospitalized again with a bad bout of influenza.

When I was recovered

I sailed again in June 1943 aboard another Dutch ship, the

SS Jan Van Goyen. While

Jan Van Goyen was in

Boston,

Massachusetts, I had the

misfortune to fall down the hold. That landed me in

hospital for another 10 days, but I was lucky that

I only had a few bumps and bruises and nothing broken.

It was around this time I found out what had happened to

the men who had been in

Veerhaven's port lifeboat.

During Da Vinci's attack the lifeboat was badly damaged and

was in

such bad condition that it would not have gotten very far.

However, it was then that the signifigance of Veerhaven's

linseed cargo

became apparent.

Veerhaven had capsized, but she did

not sink right away because the

linseed swelled up in the water and

actually helped to seal some of the holes in her hull.

When the crew in the damaged lifeboat

realized that Veerhaven

was going to stay afloat, they

clambered up onto the upturned keel. There they

remained for three

days while they patched up the lifeboat as best they could.

Then they set

forth in the fixed-up boat and after five difficult days had the

good fortune to be picked

up by a tanker from the neutral

country of Uruguay.

By the time of the

Normandy Invasion which began on June 6th, 1944,

I was serving on my 9th and last ship, the

Dutch-flagged Philips Wouwerman.

As the Allies pushed north-eastwards across Europe,

it became essential that they acquire the port of

Antwerp,

Belgium in order to

resupply their troops. The city of Antwerp was

liberated on the

4th of September, 1944, but the port could not

be used by the Allies because the Germans still held

the seaward approaches to the city along the

Scheldt Estuary.

It wasn't

until early November, after a gruelling and costly

campaign, that the Allies

secured the Scheldt. Once Antwerp

was open to Allied shipping, Philips Wouwerman

was one of the merchantmen which became involved in keeping the

vital port supplied. Even though by this time in the war

the Allied victory seemed certain, the German forces

never let up and their efforts to

prevent

our merchant convoys from reaching Antwerp intensified.

Allied merchantmen

continued to be lost to enemy

mines,

E-boats, air-raids,

midget submarines and the new

harder-to-detect Schnorkel-equipped

U-boats,

right up to the end of the war.

In the German-occupied part of Holland the final winter of 1944-45 was

so hard on the Dutch people that

many of them starved

to death before the Netherlands could be liberated.

On April 28th, 1945, a

truce was arranged between the

advancing Canadian forces

and the Germans to allow food to be brought in to the Dutch

civilians. My last

wartime convoy was involved in this

humanitarian effort and we took vital food supplies

to the Dutch port of

Rotterdam. It was a fitting way for

a Dutch merchant ship to end the war.

|