Quarantined With Smallpox

Hamor Gardner grew up far from the sea in the Canadian city of Toronto, Ontario. He became involved in the war effort right after High School in 1941 when he went to work at the Toronto Shipbuilding Company Limited, helping to build Algerine Class Minesweepers for the Canadian and British navies.

|

by Hamor Gardner

In this part of the world we haven't spoken seriously about smallpox

for decades. It was thought of as a disease that had been eradicated.

Hamor at the Wheel |

I had an experience with smallpox when I was "Chief Sparks," or radio operator, on the S/S Noranda Park at the tender age of 20 during the Second World War. I have never accepted the notion that the danger of catching smallpox is a thing of the past. I believe those deadly smallpox germs are simply lying dormant somewhere, awaiting the opportunity to invade our bodies' flimsy defences.

Out of respect for Joe McVeigh's family , I have never attempted to have this story published. However, in light of the current global situation, I believe it is time that Joe's story is known. Joe's death was not the only one. Many Canadian seamen died in India and other tropical countries during the war from preventable diseases.

It is a disgrace that Canadian merchant seamen were not immunized against diseases such as smallpox prior to sailing from Canada. In contrast, seamen in the United States Merchant Marine received the same series of shots as members of their armed forces.

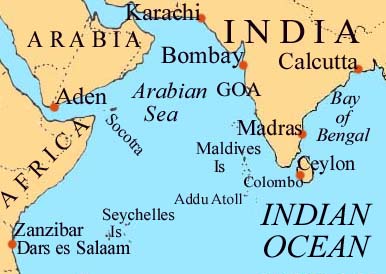

On Jan. 2,1945, a coal-burning harbour tug helped ease our Canadian merchant ship S/S Noranda Park out of the confines of Calcutta's Kiddepore Docks and into the Hooghly River channel. Whistles were exchanged and the Noranda Park began the 90-mile run to the Bay of Bengal in the capable hands of a silver-haired river pilot.

|

When we cleared the mouth of the river, with its flotsam -- as well as human corpses -- it was a relief for all hands to smell the sea air as the ship plowed a watery furrow into the Bay of Bengal en route to Colombo, the capital of what then was Ceylon and is now Sri Lanka.

The two junior radio operators, Joe McVeigh and Tom Horn, were especially pleased to be clear of the clutches of the professional, highly skilled beggars of Calcutta. Being first trippers, they had held the naive notion that they had seen it all when the ship had discharged cargo at Bombay However, they learned that the sights, smells and sounds of Calcutta made those memories diminish in comparison.

During the evening of the second day at sea, Joe said he was feeling so rotten that he couldn't stand his watch. The next morning he was laid low with a raging fever. The captain and chief steward thumbed through the ship's medical manual, searching for a clue to Joe's illness. It was little use. They decided to keep him dosed with the standard tropical remedy for shipboard complaints -- aspirin and quinine.

Joe's fever worsened as the ship inched southward. He slipped in and out of consciousness and was in dreadful shape a few days later when we rounded the southern tip of Ceylon. An urgent request for a doctor was signalled to the port authorities before the anchor splashed into the waters of Colombo harbour.

Two hours later, the port doctor arrived alongside in a sparkling white hospital launch operated by two sailors smartly togged out in whites. A huge red cross was emblazonied on the awning, sheltering its afterdeck. The portly doctor, obviously enjoying his contribution to the war effort, climbed aboard and gave Joe a cursory examination.

"It looks like a form of dengue fever Captain," the doctor explained. "Keep giving him aspirin and quinine. He should be feeling better in a day or two. I'll come out to see him tomorrow." After accepting a gin and tonic from the skipper, the doctor took his leave.

Early the next morning, I was dragged reluctantly out of a deep sleep by Tom shaking me. "It's Joe," Tom said excitedly. "Come and see him. He's covered from head to toe with a helluva' looking rash."

Pulling on a pair of shorts, I followed Tom down to their quarters on the deck below. Joe was sprawled on the bottom bunk. He was glistening with sweat, breathing in short gasps. and oblivious to what was happening. His skin was a mass of small, red, weeping blisters.

When the old man had a look at Joe, be had me blink harbour control with a request that the doctor revisit the ship immediately.

Grumbling his displeasure at being roused out at such an early hour, the doctor made his way forward. There was a distinct change to his demeanour after he looked at Joe. Taking the captain aside he whispered: 'I'm sorry to tell you, Captain, but that man has smallpox. He will have to be taken ashore and placed in quarantine."

"Smallpox. My God, are you sure?"

"Yes, it's smallpox all right. I've seen it often enough."

"Damn," the skipper exclaimed, exasperation showing on his ruddy face. "I'll get things set up right away. We should be ready to lower him into your launch in about a half hour. Is that OK?"

"No, no. no," the doctor replied emphatically "You can't do that; he'd contaminate my launch. You'll have to transport him in one of your own boats. Oh, one other thing, your ship will be in quarantine for at least 15 days."

Two of our four lifeboats were equipped with engines. The engineers didn't think much of either of them. They were too temperamental.

The chief mate opted for the starboard motor lifeboat. We brought Joe out on the ship's stretcher and set it on top of number three hatch beneath a hastily rigged tarpaulin. The heat grew more intense as the sun arced its way into the glaringly blue sky. Tom and I took turns waving a makeshift fan over Joe, and keeping damp towels on his forehead. Joe was too sick to care.

It was well after nine when the fourth engineer announced, with tongue in cheek: "Well, that sorry bloody excuse for an engine is OK, more or less."

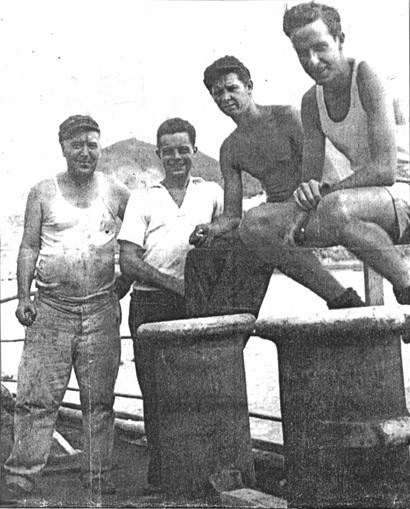

Joe was lowered into the boat. Tom and I climbed down and sat on either side of the stretcher that was resting amidships on three of the seats. With Jim Baxter, the fifth engineer; nursing the engine, and Derrick Smith, the bosun, at the tiller, we cast off.

We were barely clear of the ship when the engine conked out. Tom and I broke out a set of oars in an effort to keep the boat's head into the strong prevailing wind blowing squarely from the quarantine dock.

In the throes of his fever; his head rolling from side to side, Joe began vomiting. We tried cleaning him up as best we could during our time-outs from the oars. The sporadic vomiting continued.

Left to Right: Thomas Mooney,

Donkeyman,

Fred the

Fourth Engineer>,

Jim Baxter, Fifth Engineer and

Hamor Gardner,

Chief Radio Operator>.

Left to Right: Thomas Mooney,

Donkeyman,

Fred the

Fourth Engineer>,

Jim Baxter, Fifth Engineer and

Hamor Gardner,

Chief Radio Operator>.

|

That long, frustrating mile finally ended when we eased the boat alongside the dock. An ambulance was parked nearby with its rear doors open. Waving the two attendants aside, we made a point of carrying Joe to the ambulance ourselves.

Seeing that Joe was semiconscious, I tried cheering him up. "Have a good holiday Joe. We'll see you in a couple of days."

His prophetic reply was to stay in my mind: "Thanks for everything, fellas, but I don't think I'll be back."

With mixed emotions we watched the ambulance disappear. Reality returned when a dock attendant walked over and handed each of us a small bar of carbolic soap. "The doctor said you have to shower. Follow me, please."

He led us to an adjoining building and pointed to the crude shower facilities.

Derrick asked: "Where are the towels?" "No towels, no towels," replied the attendant.

"What an outfit," the bosun growled.

We left our shirts and shorts on. They needed washing as much as we did. They were drying in the late morning heat as we climbed back into the boat.

The return trip to the ship was a repeat of the inbound one except we were running with the wind. The engine continued to peter out every few hundred yards. Wearily, we followed each other up the Jacob's ladder.

By late afternoon the ship was anchored at the extreme northern corner of the harbour, far removed from the numerous naval and merchant ships swinging blissfully at their anchors. Our 15 days of isolation had begun.

Early that evening, the doctor and two nurses came out to the ship and vaccinated all hands against smallpox.

Daniel Joseph "Joe" McVeigh Second Radio Operator |

It was close onto midnight of the third day under quarantine when a message was brought out to the ship. The skipper called me into his quarters and handed it to me. It was typed on hospital stationery.

"We regret to inform you that the crew member taken ashore for medical attention died at 1930 hours this day."

The days in quarantine became interminably long. The near yet iIlusively distant shore was the only visual relaxation, other than the specatacular sunsets. Sounds from shore echoed out to the ship as the solitude of evening eclipsed the prevailing wind of the day. Occasional voices could be heard, the laughter of children playing, the subdued hum of traffic. Twinkling lights cast long reflections across the darkening water. Crewmen lounged against the rail or sat on hatch covers, staring wistfully at the shore.

There was a noticeable change in the crew when no one else became ill after we had been quarantined for 10 days. Greeting someone on deck turned into a ritual with comments' such as:

"Hey, you don't look too good. You sure you don't have a fever?"

"Gee, I was thinking the same thing. You look like hell."

Each passing day brought a broader smile to the doctor's well-filled countenance. After the 12th day he was convinced that no one else was going to fall victim to smallpox. His convictions proved true and the quarantine was lifted on the 16th day.

When the ship departed for Aden a week later, no one had an answer to the all-too-familiar question: "Why Joe?"

That question was finally answered. when Tom and I visited Joe's parents six months later. His family did not believe in any form of vaccination or inoculation.

Joe had never been vaccinated against smallpox.

Copyright Hamor Gardner, 2001

After the war ended Hamor married Jim Baxter's sister

Patricia and the couple raised two

sons, Ed and Doug.

Hamor tried a variety of jobs before

returning to Radio Operating again in 1953. Throughout

his career he worked

on radio beacon and light stations and marine radio coast stations

before becoming a Radio Inspector in London, Ontario and later Ottawa.

After Hamor retired in 1979 he was drawn back to

the sea and worked for a short time as a "Sparks"

aboard the vessels

Coastal Transport and

Bulk Queen.

Hamor began writing stories, often with

a maritime theme,

for

his four grandchildren, and he found that he

really enjoyed it. One of Hamor's delightful

short stories, "Mal de Mer",

is based on his experiences during his first trip to sea aboard

Tweedsmuir Park.

As well as

writing short stories, Hamor has also written

an epic poem --

Park Ship Odyssey -- which is now

in the care of the

Canadian War Museum, and

a book --

East of Suez --

which evolved from the poem.

Hamor and Patricia made their home in the

beautiful city of Amherstview, Ontario.

November 2003:

The Second World War Experience Centre

has uploaded an abridged version of Hamor's fascinating WWII memoir East of Suez which covers his time aboard

the

SS Noranda Park

and the

SS Tweedsmuir Park. To read the Centre's online version of East of Suez,

Please Click Here.

|

August 10th, 2007: I am very saddened to report that Hamor passed away suddenly

last month at the age of 82. Hamor was a wonderful man

and I feel so fortunate to have known him. Hamor touched so many lives and he will be

sorely missed by everyone.

I am so grateful that with his wonderful stories, Hamor has left us all a lasting legacy.

Maureen Venzi

|

Hamor's page is maintained by Maureen Venzi and it is part of The Allied Merchant Navy of WWII website.